We would not be born out of sweetness, we were born out of rage, we felt it in our bones.

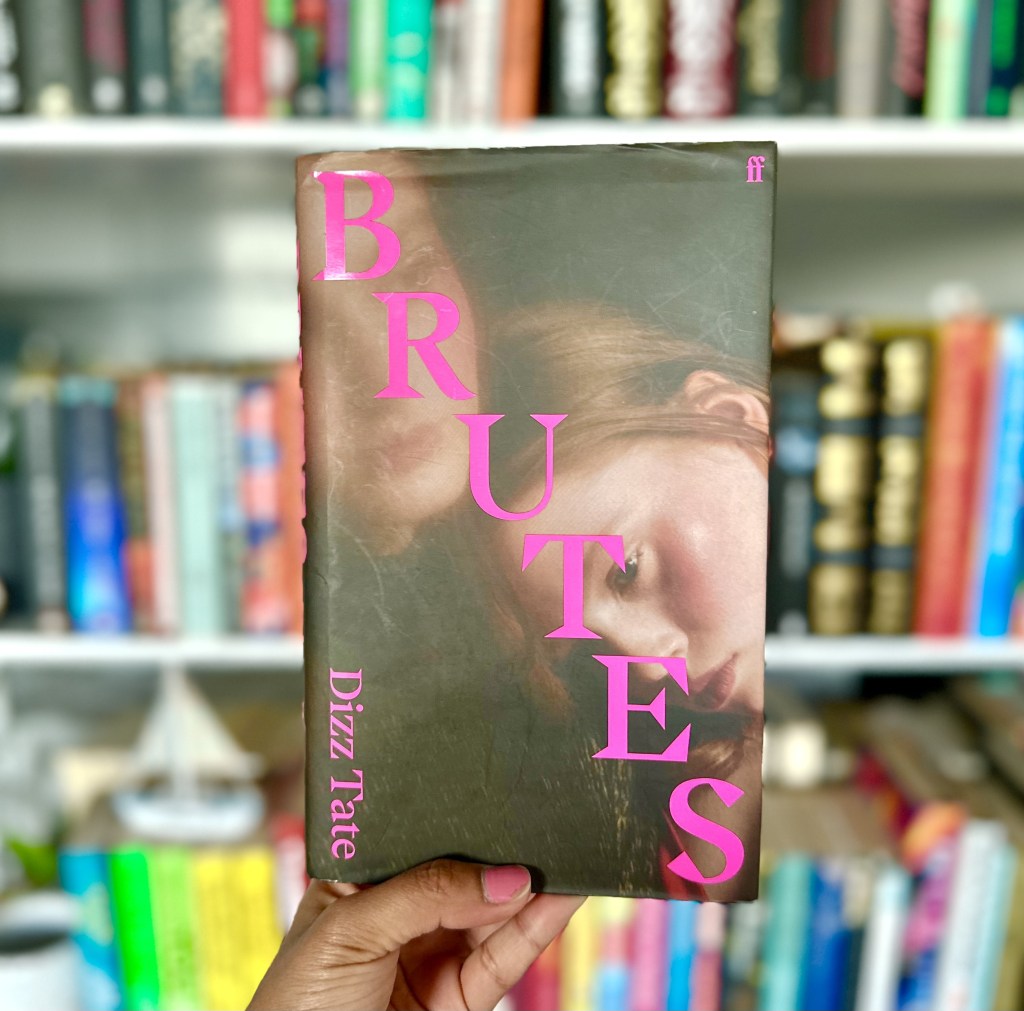

In Falls Landing, Florida—a place built of theme parks, swampy lakes, and scorched bougainvillea flowers—something sinister lurks in the deep. A gang of thirteen-year-old girls obsessively orbit around the local preacher’s daughter, Sammy. She is mesmerizing, older, and in love with Eddie. But suddenly, Sammy goes missing. Where is she? Watching from a distance, they edge ever closer to discovering a dark secret about their fame-hungry town and the cruel cost of a ticket out. What they see will continue to haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Through a darkly beautiful and brutally compelling lens, Dizz Tate captures the violence, horrors, and manic joys of girlhood. Brutes is a novel about the seemingly unbreakable bonds in the “we” of young friendship, and the moment it is broken forever.

Rating: 4.0/5.0

Brutes explores the bonds and perils of girlhood. It echoes coming-of-age novels like The Virgin Suicides and We Were Liars. In a hypnotic, collective voice, the story is narrated through the first person plural, immediately establishing the co-dependent relationship of the five girls (and one boy, who ‘became a girl’ when he was accepted by the girls). The use of the first-person plural was one of the most interesting aspects of the novel. It gave the prose a lyrical and choral voice that made the story hypnotic and had me gripped from the first page.

Sammy Liu-Lou, the preacher’s daughter’s, disappearance is the outset of the novel but her mysterious disappearance remains just that, a mystery. The main focus is on the girls who have formed an unofficial fan club for Sammy and watch her with admiration from afar.

I enjoyed seeing snippets of Sammy through the girls’ eyes. There is an intrigue they hold at the way Sammy defies the rules of girlhood that have been taught to them, like when she cut her hair off. They reflect that they ‘hid [their] faces because [they] were certain someday, someone else would reveal them back to [them]…tell [them] how beautiful [they] were, had been all along in secret.’ I remember a similar sort of admiration towards a girl in my own girlhood, when she came to school one day with a pixie cut.

Their watching gives them a ‘brutal power’ and Tate establishes the key element of their voyeurism as she writes ‘we always know where Sammy is’. Their collective narrative is broken up by Tate through a series of first person narratives in between, flash forwarding into each girl’s future and demonstrating the impact of their girlhood experiences. The girls grown-up individual narratives provide unsatisfying and realistic accounts of how their lives have turned out.

The watchful, voyeuristic behaviour of the girls is perverse and their collective fascination with Sammy establishes some of the group’s beliefs and rules their behaviours. The express their fears and vulnerabilities as a hive mind, such as how they ‘are scared of being alone’ but simultaneously pick on each other with a type of cruelty only teen girls can inflict on their each other. As a hive mind, they know what their deepest insecurities are and how they can hurt each other the most before taking them back into the fold again. Rejection from your friends is harsher than anything else at that age.

They revel in the power of hurting each other, themselves, and their mothers. There is something very unsettling and cutting about a group of young girls who actively attempt to hurt and fight with their mothers, especially ‘when [they] acted like men.’ They are frightened of being ‘fatherly’ and fear the idea of becoming like their mothers. I enjoyed the exploration of strained mother-daughter relationships, reflecting on how young girls idolise their mothers before their animosity and viciousness take over.

They are always the observers, watching their town, their mothers, the other girls, and yet they have a yearning to be watched themselves. They seek fame through the town’s Star Search scouts and want to be admired the same way Sammy is by them.

Tate’s writing is expressive and atmospheric. There is a sense of magical realism that captures the narrative’s essence of being told through a young girl, who doesn’t understand the horrific thing that’s happened to her without exploiting the trauma. The abrupt break from the use of ‘we’ to ‘I’ is horrifying as you begin to realise what is happening to one of them and how helpless they are in this situation. As the narrator says, ‘I look around for someone else to be but I am alone and I have always been so scared of being alone,’ the sense of protection that comes from the collective is broken and forces them into their individual identities.

As the events of the novel unravel towards the last quarter, there is no satisfactory conclusion. I closed the book with a lot of questions in mind, but the lingering confusion feels intentional.

Leave a comment